Το ιστορικό της ελληνικής κρίσης χρέους (Greek debt crisis). Ήταν τελικά επιτυχημένη η συνταγή;

Ιn our previous article, highlighted Greece’s financial irresponsibility, revealing that in the late 20th century, the country used debt to fuel superficial economic growth, which did not support local production.

Instead, funds were predominantly spent on importing goods and sustaining a bloated public sector, which reinforced clientelistic relationships between the government and Greek voters. As the new decade began, Greece continued its fiscal irresponsibility, exploiting the easy access to funds that Eurozone membership provided, thereby deepening its financial predicament. It is already established that by 2005, due to misreported financial data, Greece came under fiscal monitoring by the European Commission. At that time, Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 127.55%, with inflation at 3.55% and a budget deficit of 6.20% of its GDP—clear indicators of a country in severe financial distress, deviating significantly from the standards set by the Growth and Stability Pact, which was a less stringent agreement than the Maastricht constraints, where fiscal divergence could lead to exclusion from the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). So why didn’t the eurozone initiate the bailout program and impose the strict reforms and sanctions needed for Greece to regain solvency in 2005? Why did they wait five more years until the financial “ticking bomb” of Greece’s economy imploded?

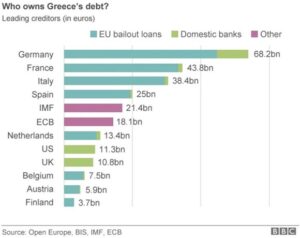

To understand the Eurozone’s lack of immediate action regarding the Greek economy, additional context is necessary, particularly concerning the activities of the Eurozone’s major powers and Greece’s lenders. In 2005, a substantial portion of Greece’s debt was held by major French and German banks.

Concurrently, both France and Germany were exceeding the Maastricht Criteria’s spending limits.

Imposing sanctions on Greece would have required the EU to also enforce austerity measures on France and Germany to avoid accusations of hypocrisy. Such a move was unappealing to the major powers of the Eurozone, as it could destabilize and weaken the euro, particularly at a time when the Eurozone was attempting to attract other significant countries like the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Sweden to adopt the euro. Hence, no sanctions were imposed on Greece by the Eurozone at that time.

As previously mentioned, the fragile Greek economy’s downfall was triggered by the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, exacerbated by Greece’s admission in 2010 that it had further misreported crucial financial data. By 2010, Greece was effectively shut out from the international bond markets. The country’s debt-to-GDP ratio soared to approximately 180%, and its budget deficit exceeded 15% of its GDP—more than four times the EU standard. The reason the Eurozone refrained from allowing Greece to default—a discussion of whether this would have been a better outcome is separate—was principally to avoid severe impacts on major banks and Eurozone countries that held Greek debt (for example, Finland’s share of the debt amounted to 10% of its annual budget). The potential default risked weakening the euro and raising fears of contagion.

To prevent a sovereign default, the European Commission, European Central Bank (ECB), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) (collectively known as the Troika) initiated a €110 billion bailout loan to support Greece until June 2013. This support was contingent on Greece implementing austerity measures, structural reforms (including making the Greek Statistical Office independent to prevent future misreporting of financial metrics), and privatizing government assets. Part of this bailout plan included the unprecedented Security Market Program launched by the ECB, which allowed the ECB to purchase government bonds of struggling sovereigns like Greece on the secondary market to bolster market confidence and prevent further sovereign debt contagion throughout the Eurozone. This program was part of a broader €750 billion rescue package agreed upon by finance ministers for struggling Eurozone economies. The bailout funds were primarily used to service maturing bonds and to finance ongoing annual budget deficits. The imposed austerity measures included tax increases, pension reductions, public sector wage cuts, and deregulation to enhance competitiveness and growth. Initially, the plan appeared successful as yields on Greek bonds decreased, and Greece managed to reduce its deficit to 5 percent of GDP. However, the fiscal consolidation had a detrimental economic impact, and Greece’s economy continued to suffer.

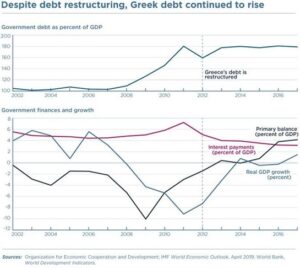

More specifically, Greece’s GDP decreased from $297 billion in 2010 to $242 billion, while the debt-to- GDP ratio rose from 144% in 2010 to 162% in 2012, plunging its economy into an even more precarious situation than before. The only positive development was the reduction of the budget deficit to a still problematic 1.8% of GDP. In the fourth and final review of Greece’s first bailout program, the troika of institutions—the ECB, IMF, and European Commission—warned of a slackening in reform implementation and a recession that was worse than expected.

This situation sparked fears that Greece might exit the euro, potentially triggering a major financial crisis in the Eurozone and destabilizing the euro as a currency. For this reason, a second EU-IMF bailout program worth €130 billion (approximately $172 billion) was created for Greece in 2012, which included a 53.5 percent debt write-down—or “haircut”—for private Greek bondholders. Most investors went along with this arrangement, as the alternative would have been a default, resulting in the loss of their entire investment. In exchange, the Greek government received a new package of official emergency loans to be disbursed in tranches over three years, enabling it to cover its expenses while continuing with budget cuts. This restructuring was the largest debt restructuring in history. Later in 2012, the terms of the second bailout loan were revised to include lower interest rates on Greek bailout loans and a new debt-buyback program.

This new bailout program, along with the additional austerity measures, initially seemed to work to some extent. In 2013, Greece achieved a small primary fiscal surplus (the fiscal balance excluding interest payments). However, the Greek economy as a whole continued its steep decline, with GDP down by 25% from 2010, unemployment reaching 27% (and an alarming 58% for those under 25), and the debt-to-GDP ratio increasing to a daunting 180%.

A positive aspect of these two bailout programs was that the debt came to be owned predominantly by various public European and international institutions, such as the European Financial Stability Facility, the European Stability Mechanism, and the European Central Bank, rather than by private bondholders.

In 2014, Greece returned to international financial markets with the first issue of Eurobonds in four years, managing to raise 3 billion euros from five-year bonds at a yield below 5%—a small sign of a return of investor confidence. In 2015, a new anti-austerity government led by Alexis Tsipras of the left- wing Syriza party demanded more debt relief and less fiscal restraint. The Eurogroup declined, and this confrontation reignited the crisis. Europe wanted to extend its loans to prevent Greece from defaulting or leaving the euro, which could potentially provoke a new banking and economic crisis, but at the same time, it was unwilling to yield to Greece’s demands. After Greece declined further economic support from the Eurogroup that was tied to increased financial discipline, the ECB refused to extend additional emergency liquidity to Greek banks. This, combined with a run on deposits, forced the Greek government to impose capital controls and cash withdrawal restrictions. Greece also missed its 1.6 billion euro ($1.7 billion) payment to the IMF when its bailout expired on June 30, becoming the first developed country to effectively default to the Fund. This crisis pushed both sides to compromise in August 2015, when Greece agreed to a new reform program in exchange for immediate cash and the promise of up to €86 billion over the next three years. This new reform program was slightly less austerity-heavy than previous propositions.

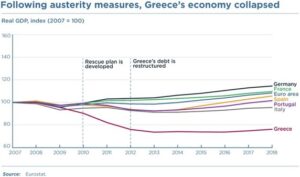

After the third program started, Greece exceeded expectations by posting a large primary surplus of almost 4 percent. Unemployment began a slow decline, and growth returned to positive territory in 2017. In mid-2018, Greece’s creditors offered further maturity extensions and interest deferrals after strong suggestions and disagreements from the IMF, which believed that the country’s debt was unsustainable and that those beneficial measures were needed. 2018 was also the year when Greece received the final loan of the third bailout program, although strict financial monitoring continued until 2022. In 2018, Greece’s GDP was 180 billion euros, with a debt-to-GDP ratio standing at an alarming 208%. After three bailout programs, many reforms, and numerous austerity measures from 2010 to 2018, Greece managed to lose one-third of its economic output and suffered the longest recession of any advanced capitalist economy while still having an unsustainable amount of debt. Certainly, political turmoil that slowed the implementation of necessary reforms did not aid Greece’s and the Eurozone’s attempts for an economic turnaround, and while Greece’s economy still exhibited many of the inefficiencies described in the previous article, there were also mistakes on Europe’s side.

Greece was not allowed to default on its debt in 2010 because such an event would have had an extremely negative impact on the Eurozone. Many significant French and German banks, which held most of the Greek debt at that time, would have also faced default. This scenario changed with the bailouts; thereafter, most of the Greek debt was owned by major financial institutions. These institutions had financial ties that primarily affected countries like Germany but did not burden their banks as much.

Additionally, there were fears of contagion and another major financial crisis in the Eurozone, which would weaken the euro.

Moreover, Germany benefited from the crisis through an influx of investments, as it was seen as one of the safest countries, and enjoyed a boost in exports thanks to the euro’s depreciation. However, this does not imply that Greece would have been better off defaulting or exiting the euro (Grexit), since its economy was still mostly plagued by deep structural problems, lack of competitiveness, deteriorating finances, and corruption.

There were undoubtedly political maneuvers to prevent Greece from defaulting, and there was certainly a degree of hypocrisy on Germany’s part. Germany advocated for measures that it did not strictly adhere to, such as maintaining large primary surpluses or following the Maastricht criteria as previously described. Nonetheless, it is clear that Greece would not have benefited from defaulting. The harshest criticism of Greece’s creditors should focus on the bailout programs themselves. For instance, after the first bailout program, market confidence was not restored; the banking system lost 30 percent of its deposits, and the economy fell into a much deeper-than-expected recession with exceptionally high unemployment.

Generally, Europe adhered to the Expansionary Fiscal Contraction (EFC) theory, which “predicts that under certain conditions, a significant reduction in government spending—such as austerity measures— will change future expectations about taxes and government spending, thereby expanding private consumption and resulting in overall economic expansion”. However, this theory, which necessitated harsh austerity measures, proved extremely inefficient in Greece and other countries, as indicated by the severe economic contractions that failed to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. The only positive outcomes were debt restructuring, some important structural reforms, and a heightened focus—albeit excessive and negatively impactful—on maintaining primary budget surpluses.

Despite the severe challenges and criticisms, the Greek crisis highlighted the need for more balanced economic policies and greater solidarity within the Eurozone to prevent future crises and foster sustainable growth across all member states.

Author: Άγγελος Λαγός